Rise and decay of the Tolerance principles from Voltaire to our days

Invited by the Atheist Society of India (ASI): our lecture tour in India 2005

Tolerance, once the essence and the backbone of the European Enlightenment movement, seems no longer to be »in«. On the contrary, it seems to vanish from Earth. It is not only the Islamic countries, since Khomeini’s rise to power, that, in our time, initiated openly denying the Tolerance principle and the corresponding state secularism that had been the key trait of any modern vs. medieval state; it is not only the USA that foster and protect Christian fundamentalist movements and ideologies, nor is it a speciality of the BJP struggling for a Hinduist revival. The truth is: intolerance, especially religious intolerance, is a global, worldwide tendency within the last decades. In spite of all praise of the »modern secular society«, tolerance is no longer modern. Life and death of religious leaders, e.g. the Roman Pope, meet more public attention than life and death (and even insights and achievements) of scientists and other serious people. But what is worst: the very idea of Tolerance seems to become extinct, only perversions of it survive, its meaning having been shifted to the contrary of its original sense. Even many atheists did not escape that decadence; some of them even straightforwardly are advocating intolerance against religions, provided those religions are small, weak and recent, whilst misinterpreting tolerance as something like shielding big and powerful religions from any pungent and effective criticism.

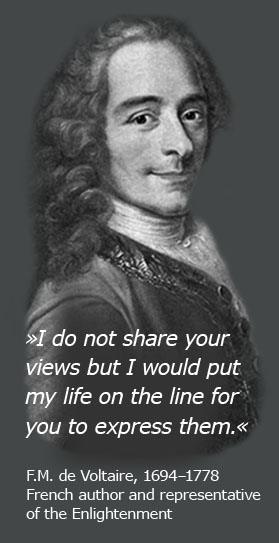

There was no such problem when the Enlightenment movement was blossoming and authentic. Voltaire, its undoubted leader, put it thus: »I do not at all share your opinion, and I will always oppose it; but I am ready to die for your right to freely express it.«

So tolerance did not mean something like politeness or abstinence from criticism; but it did and does mean abstinence from (and absence of) violence or similar unfairness in the discussion. It also does not mean excluding someone from the debate (»not giving a forum«, as modern newspeak calls that), but, on the contrary, it meant giving everybody a forum, but to nobody the freedom of evading the argumentation – under fair conditions, as always. »Forum« means literally »market«; and exactly that was meant by the Enlightenment movement and Voltaire himself: everybody may try to sell his goods on the market of opinions, nobody is excluded from it, and everybody has to pay the same fee for the same table, not the weak one a high to excessive fee, the strong one a low to symbolic fee; and nobody is urged to buy the goods. And furthermore, and of course: tolerance does not mean freedom to commit crimes, even if these crimes as lapidations, circumcisions, flagellations, etc. are inspired by religions; the very core of Enlightenment was and is the equality of all citizens before the law, and therefore their equal treatment by the state, especially when religion is concerned: no exemptions for big and old religions, no severity against small and new ones. For Voltaire and all his companions nothing was more self-evident. This was and is tolerance genuine.

Consequently, Voltaire and all his fellow fighters always – and very courageously – defended all religious minorities of their time and country, though, of course, they did not at all share their doctrines. These were the Quakers (whose community Voltaire visited in England), a very recent and heavily persecuted sect of that time, and especially the French Calvinists (= Huguenots) or, to say it more precisely, the tiny part of them that had survived Louis’ XIV holocaust-like persecutions that had made France lose more than 20 % of her population. But – what Voltaire could not know – the nefarious French Government of his time planned and secretly designed a second and final holocaust for the survivors by an extremely detestable method that sounds very modern: the surviving victims were to be falsely accused of invented crimes and then to be individually put to capital punishment. All this came to light after the French Revolution that did not only and firstly bring the authentic Human Rights to mankind, but also opened the secret archives of the state. So that infamous plan came to light resp. to the knowledge of mankind; it was Voltaire, the single man with no other weapon than his pen, who prevented it from being carried out, thus saving thousands of innocent people from cruel deaths.

For the sinister French Government had already finished its dress rehearsal for this detestable plan and killed a Calvinist citizen called JEAN CALAS by sentencing him to death by dismemberment on the ground of a false murder accusation. Jean Calas was cut into pieces, Voltaire could not help him personally; but he launched a long-term publicity campaign over most of Europe, finally forcing the French state apparatus to rehabilitate Jean Calas. By this – and only by this – the French mock trials were stopped immediately after beginning, and tens of thousands of French Calvinists were saved from bloody extinction; their descendants are still to be found, other than those of most European Jews, and make up about 3 % of today’s French population.

Where do we find today’s atheists defending today’s Quakers and other sects in trouble, that are discriminated by governments and denigrated by the media, where are today’s advocates of Tolerance in favour of Scientologists, Neo-sanyassins or Raëlists, to name but a few? Why do today’s freethinkers concede freedom of thought (and organisation) only to themselves and to their own powerful enemies, who do not need their help or that of anybody else, denying it to those who really need it? Why are Voltaire’s spiritual descendants, as modern atheists might call themselves or claim to be, meanwhile that unworthy that they do not too seldom help the big churches to hound their recent competitors instead of defending them as Voltaire did, why do they advocate intolerance against the weak and practise tolerance against the strong and really dangerous?

Of course, this decomposition of a once brilliant, if not venerable, string of thought and action is rooted ultimately in historical and social facts and changes. But directly those hidden causes are mirrored by decomposition and perversion of the tolerance concept itself. For understanding this we have to look back to the origins.

Why did Voltaire and all his fellow fighters from d’Alembert to d’Holbach defend all sects of their time without any restriction against slander and persecution, against Church and State? Did they secretly share their opinions and doctrines? Were they simply not radical enough, because really radical atheists will always help the Pope and his allies against independent competitors?

The true reason, of course, for Voltaire’s and his fellow fighters’ behaviour is very simple: they wanted to win, and they were sure they were right. They expected – and they were right with that – that in a discussion fenced off from violence, inequality and dirty tricks – and nothing else than such a discussion tolerance does mean, at least substantially – there will be the highest probability that the side that is right will win. The representatives (and carriers) of religion share this opinion, and that is why they do not appreciate tolerance. For they know either very well or deep in their heart that they are not right and therefore, when confronted with reason, but cut off from violence (a state that closely to inevitably will be the result of tolerance), they will lose. And even if a religion is not confronted with reason, but with another religion, under the condition of tolerance the result will be rather similar. Religions then will soon appear as their mutual parodies, and therefore, in the long run, one of them will destroy the other. That is why the representatives of Enlightenment were of the opinion that if religions do exist, there can not be enough of them (just as imperialists think that there cannot be enough »independent« states in the world outside their own state that, of course, should remain as big as possible).

Why were Voltaire and his companions so sure that they were right? Because they fought for civil instead of feudal rule, and feudalism was not only closely linked and interwoven with religion, but also all rational arguments spoke in favour of civil rule, whilst feudal rule could not be successfully defended rationally. But after civil rule and the original Human Rights once were established by the French Revolution, it soon became clear that the new social system that just as the toppled one made a tiny class of people rich, mainly by inheriting resp. heritage, and left the majority of the people poor and dependent, was not so easily and entirely to be defended by reason as expected, and, therefore, the abolished privileges of religion were restored, maybe partly, whilst the distance between the new – and normally rich – carriers of civil rule and their own anti-feudal and anti-religious allies, the peasants and the industrial workers whose numbers steadily increased, grew from year to year, especially after the workers’ movement gained ground and shape, and its members also learnt to argue rationally. The new rulers thus lost their Reason monopoly. And consequently their fervour for tolerance cooled down.

As an epistemological consequence, the meaning of the word »tolerance« became twisted. It no longer meant what the Enlightenment had based its programme upon, but was watered down to something like »indifference« – or, even worse, »Sarva Dharma Samabhaava« –, in fact, the opposite of its original meaning. For what purpose should somebody, e.g. Voltaire, die as a martyr for liberty of speech by fencing off violence from discussion, when people were encouraged to be indifferent to the result of that discussion?

As early as in Freud’s times this perversion had already broadly evolved, as his following complaint shows:

»What further claims do you make in the name of tolerance? That once someone has uttered an opinion, which we regard as completely false, we should say to him: ›Thank you very much for having given voice to this contradiction. You are guarding us against the danger of complacency and giving us the opportunity in showing the Americans that we are really as »broadminded« as they always wish. To be sure we do not believe a word what you are saying, but that makes no difference. Probably you are just as right as we are. After all, who can possibly know who is right? In spite of our antagonism, pray allow us to represent your point of view in our publication. We hope that you will be kind enough in exchange to find a place for our view which you deny.‹ In the future, when the misuse of Einstein’s relativity has been entirely achieved, this will obviously become the regular custom in scientific affairs. For the moment, it is true, we have not gone quite so far. We restrict ourselves, in the old fashion, to putting forward only our own convictions, we expose ourselves to the risk of error because it cannot be guarded against, and we reject what is in contradiction to us. We have made plentiful use in psychoanalysis of the right to change our opinions if we think we have found something better« (SE XXII 144).

Some time later the ideological function of empiriocriticism as a doctrinal consequence of that twisted »tolerance« became even clearer to him (though he somewhat misleadingly does call empiriocriticism »anarchism«):

»The first of these Weltanschauungen is as it were a counterpart to political anarchism, and is perhaps a derivative of it. There have certainly been intellectual nihilists of this kind in the past, but just now the relativity theory of modern physics seems to have gone to their head. They start out from science, indeed, but they contrive to force it into self-abrogation, into suicide; they set it the task of getting itself out of the way by refuting its own claims. One often has an impression in this connection that this nihilism is only a temporary attitude which is to be retained until this task has been performed. Once science has been disposed of, the space vacated maybe filled by some kind of mysticism or, indeed, by the old religious Weltanschauung. According to the anarchist theory there is no such thing as truth, no assured knowledge of the external world. What we give out as being scientific truth is only the product of our own needs as they are bound to find utterance under changing external conditions: once again, they are illusion. Fundamentally, we find only what we need and see only what we want to see. We have no other possibility. Since the criterion of truth – correspondence with the external world – is absent, it is entirely a matter of indifference what opinions we adopt. All of them are equally true and equally false. And no one has a right to accuse anyone else of errors.

A person of epistemological bent might find it tempting to follow the paths – the sophistries – by which the anarchists succeed in enticing such conclusions from science. No doubt we should come upon situations similar to those derived from the familiar paradox of the Cretan who says that all Cretans are liars. But I have neither the desire nor the capacity for going into this more deeply. All I can say is that the anarchist theory sounds wonderfully superior so long as it relates to opinions about abstract things: it breaks down with its first step into practical life. Now the actions of men are governed by their opinions, their knowledge; and it is the same scientific spirit that speculates about the structure of atoms or the origin of man and that plans the construction of a bridge capable of bearing a load. If what we believe were really a matter of indifference, if there were no such thing as knowledge distinguished among our opinions by corresponding to reality, we might build bridges just as well out of cardboard as out of stone, we might inject our patients with a decagram of morphine instead of a centigram, and might use tear-gas as a narcotic instead of ether. But even the intellectual anarchists would violently repudiate such practical applications of their theory« (SE XXII 175).

And in more recent times, when »Tolerance« was watered down to meaning »accepting anything irrational when there is power behind it«, Herbert Marcuse stated – in his famous essay »Repressive Tolerance« – that this tolerance ideology (vs. the original substance of the word, i.e. tolerance) had become a means of repression (after having started as a non-ideological means of liberation).

Modern atheists, in our time of Reason’s decay and Religion’s rise to new power, should be aware of this long journey of the once so noble notion of tolerance to its very counterpart in meaning and function. To avoid becoming the useful idiots of their natural enemies, atheists – or freethinkers or whatsoever they prefer to be called – should do everything to return to their Voltairean roots.

Dr. Fritz Erik Hoevels (Psych.), Germany